ATC’s Clinical Team was honored to present at the 2018 Layton, Utah Regional NATSAP – National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs Conference on “When Young Adult Treatment Gets ‘Messy’: Coaching Parents on Boundary Setting and Detachment.”

Click to view the presentation.

It was one of many successful BREAKOUT SESSIONS at the conference.

Ryan Forbes, MS, CMHC; Program Director; Mike Hench, MS, MBA, LMFT; Clinical Director; Mark Noe, CMHC; Clinician; and Jennie Pool, CMHC; Clinician, all participated in the panel.

What was really trying to be conveyed is the difference between automatically going into “saving mode” and how to find the balance in helping our parents be comfortable while their young adult child.

– is uncomfortable.

How to be a parent in 2018:

Make sure your children’s academic, emotional, psychological, mental, spiritual, physical, nutritional, and social needs are met while being careful not to overstimulate, under stimulate, improperly medicate, helicopter, or neglect them in a screen-free, processed foods-free, GMO-free, negative energy-free, plastic-free, body-positive, socially conscious, egalitarian but also authoritative, nurturing but fostering of independence, gentle but not overly permissive, pesticide-free two-story, multilingual home, preferably in a cul-de-sac with a backyard and 1.5 siblings spaced at least two years apart for proper development, also don’t forget the coconut oil.

How to be a parent in literally every generation before ours:

Feed them sometimes.

Addressing failure to launch as a parent in 2018….

YOU GOTTA MOVE OUT…

WHEN YOUR PARENTS GIVE YOU THE BOOT

With young adults, it is important to understand how crucial it is for parents to set boundaries.

With young adult treatment, there are a lot of clients that come in with parents that are solely worried about the outcome of the child’s treatment and their young-adult child’s involvement in said treatment. For any type of successful outcome, however, the entire family unit needs to be involved in the therapy and work together as a unit.

RECOMMENDED READING

- When Our Grown Kids Disappoint Us: Letting Go of Their Problems, Loving Them Anyway, Getting on with Our Lives -by Jane Adams, PhD

- Setting Boundaries with Your Adult Children: Six Steps to Hope and Healing for Struggling Parents -by Allison Bottke

- How to Stop Enabling Your Adult Children: Practical Steps to use Boundaries and get your Power Back as you Stop Enabling -by Melody Devonish

“When Our Kids Disappoint Us” is about 15 years old now, but is still very relevant. ATC gives a copy to all the parents and encourages them to read. Interestingly, a lot of parents will reject the word “disappoint”, as if they failed somehow. Really through our treatment and through family therapy, we want parents to figure out what their life is about – what do they want?

FAMILY SYSTEMS THEORY

Homeostasis — The tendency of a family system to maintain internal stability and resist change.

If you are a Licensed Marriage Family Therapist, you probably have heard of this example of how the family unit works. What we deal with a lot, is our clients coming from a chaotic family unit:

Let’s say you have your home thermostat set to 75 degrees. If you leave the door open in St. George, UT — you will have that AC unit pumping hard to keep it there. When one of the members of the family is not well, it will affect the entire unit. Family systems have a natural tendency to resist the change from trauma, chaos, and conflict in order to try to stay at normal homeostasis.

Specifically, homeostasis is where that family system is going to try to sustain stability.

In this analogy, the problem family member acts as the open door and the family system acts as the overwhelmed AC unit.

Second-Order Change involves not just behavior, but changes, or “violations,” of the rules of the system itself.

For instance, one individual in the system can create a ton of change in the rest of the group. They can cause others to make bad decisions. However the young adult is doing in treatment, the parent can still make adaptions in the adult-to-adult child relationship. If you create change in that system, they – the young adult can either adapt or reject and push away.

Any significant change by a family member (parent) means change for the whole family system.

- As parents change, the child will attempt to return to homeostasis.

- As parents maintain boundaries (second-order change) the child will be forced to adapt.

- Once the child accepts that homeostasis in no longer possible individual change is more likely to occur.

KEY POINTS SUMMARY

- See the family system as the identified patient, not the young adult solely as the IP.

- The key to effective treatment with young adults is coaching and supporting parents to make their own transition from parenting a child/adolescent to an adult.

- The degree to which the parents change is directly correlated to young adult treatment outcomes. Sometimes successful outcomes may not reflect improved health and independence on the part of the young adult. Successful outcomes may just be the degree to which the parents are able to hold boundaries, detach, and no longer enable.

As a clinical team, viewing the identified patient ‘as not just a kid sitting in the office’ — but, rather, seeing the entire family unit as the patient is the goal.

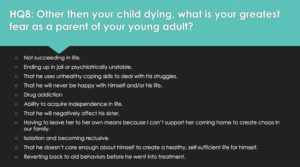

Unfortunately, there are some really bad outcomes that happen — for instance, in extreme cases, clients can even die in treatment. This is something that is conveyed to parents upfront and a grave reminder just how important their involvement is regarding their son or daughter’s recovery.

As far as sending their child off to a faraway treatment program, It is good for moms and dads to understand that it is OK for them to be grateful for some respite from their child and giving themselves a chance to be able to regroup. This can help them process and learn how to hold boundaries with someone with a severe mental health issue. These sort of boundaries are very different from being a parent and holding boundaries with a young adult with substance abuse issues. For instance — a family that has two sons dealing individually with each disorder — they will have to adapt to different rules for different sons. Even if their are not the best outcomes for the sons, the parents can still be ecstatic about the progress they make themselves.

This process of treatment, of healing, is a lot about parents regaining their lives back from constant chaos and putting the kids first. During this time, we like to let parents know to get off of social media, get off the phone, detach and get that vacation.

CASE STUDY: FRITZ

- 22-year-old male

- Parents are German and migrated to Mexico after WW2. First-generation American residing in Florida.

- Not adopted. Parents are married. 3 siblings. He is the second youngest.

- Attended a young adult wilderness program where he attempted to walk out multiple times. Eventually ended up walking out and was dropped at a homeless shelter in St. George.

- Upon intake: paranoid, very rigid cognitively, defensive, avoidant

Fritz came in presenting very fragmented. He was showing schizophrenic behaviors.

- He talked about how traumatic it was to leave to be put into the wilderness… he was paranoid. He was claiming that when the Wilderness program dropped him at the homeless shelter, they had poisoned him. He just had all-over-the-place thinking.

- He does have anxiety. His paranoia trapped his parents — “I’m sick, I don’t want to do college”. He is pretty competitive. The energy he is putting into getting his parents to let him take a break from being an adult is significant.

- The patient really was with the parents AND the son. We had t0 exhaust his ability to manipulate the parents before anything else. These are difficult conversations with the parents, especially if they don’t hold their line. For instance, Fritz was so against treatment that the father wanted to take the RV for the next year and just cuddle with him. Obviously, this would keep his son in this terrorist mode. Coaching the parents on the ability for them to not be maneuvered was the most difficult part of this case.

What is interesting is the original failure to launch issue just kept getting compounded and repeated with Fritz. No matter what program he was in, in his mind, there was a reason he shouldn’t be there and he would find ways to convince his parents to pull him out. In order for any treatment to be effective, his placement needs to be set and he needs to understand that he can’t change it.

With a kid like this, If you keep moving his placement, he is going to keep pressing the issue over and over. We tell the parents to hold a strong line and just say – “we trust the people who you are with and where you are at and what you are going to figure it out. You can pay yourself if you want to be somewhere else – you do have a choice. Although understand, your phone will get turned off, your food will be on you, there will be other bills… etc.” His resistance to doing any of this was severe.

Financial responsibility is always a big issue with this demographic and it is something we address.

Every family is different. Sometimes in these cases with the parents, it has to be a process of building trust with the program and the therapist before they start to implement the feedback. Some are just like “fix my kid” and check out of treatment themselves. Then what happens are these parents wonder why nothing is changing with their child — well half the work isn’t being done.

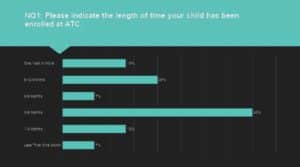

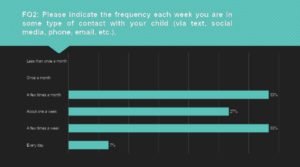

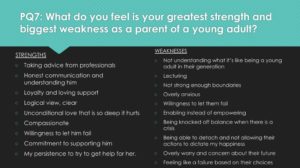

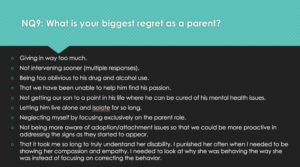

PARENTING YOUNG ADULTS SURVEY

ATC recently did a 10-item survey that was given to parents of all current students at ATC regarding parenting practices with their young adult child.

- 40% are there 3-6 months

- 13% over a year

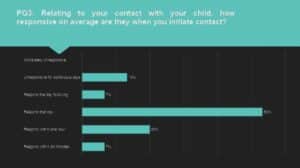

- 33% are in contact a few times a week

- 33% are in contact a few times a monthThis is indicative of how we coach parents through now having an adult to adult relationship. We wanted to see what the relationship is like now that the structure of programming isn’t so strict. like wilderness or rtc.trying to coach parents on being ok with a lack of contact – especially on day to day basis. Voicemails don’t work! LOL main means is texting or social media.

- 53% responded the same dayMales can go weeks without talking to parents. Sometimes parents get a little needy and are needing that communication. There have been crazy text message conversations with kids with all caps and have to coach parents to not respond. Its harder for kids to be accountable through texting and being rude — if you can’t talk to me appropriately, the conversation is done. Hang up the phone, end the conversation. “I love you but this relationship will be hurt with the way you are treating me”.

Parents can start to spin out on there own without constant communication. 18 years of caretaking can do this, it’s normal. But that is something to work on with their anxiety and boundaries.

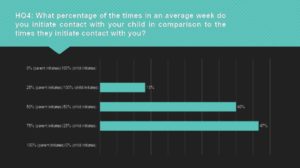

- 47% said they initiate contact 75% of the time

- 40% said their child initiates contact 50% of the timeUsually, parents have a stronger need for the kids to be in their lives then the kids want the parents in their life. And that is OK. It’s just the way it is. Sometimes we expect our children to give us so much back, and it is not fair.

Feedback for parents is to show them how engulfed they are in their kid’s life. Like, show them who they reach out to and who they have as friends and can bounce things off of.

What is the quality of communication? why are they initiating contact? “I want….” coaching parents on realistic expectations about their child. Have qualitative conversations rather than quantitative conversations — avoid the logistics only — how much, how often.

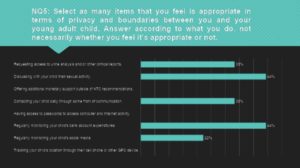

It is important to teach our parents what is appropriate in this particular family dynamic. A lot of times parents like to focus on what their child is doing and where they are located. Actually doing family therapy is different than just going over logistics.

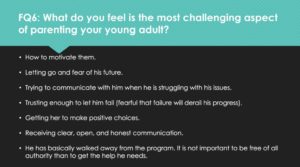

- “How to motivate my child” is the number one answer

We ask parents and siblings to take some of these mental health assessments along with the patient. Treatment is like learning a new language on both sides – for the parents and the child. Creating a new language between the two sides is often what happens.

There is no such thing as failure in treatment, just a combination of processes that don’t work together.

Remember, nothing is mandatory – they are adults – we don’t make them do anything. There is always a choice.

For parents understanding autism, for instance, watching their adult child fail or refuse to take care of themselves is difficult — Having their child in a system and a schedule is important. In this case, a parent’s first question that always comes after a few weeks of treatment is, “is he/she brushing their teeth?”

There is nothing linear about what we do. There is not a way to just do 1,2,3 steps and ready to go!

A big step is having parents come to terms with where their young adult is. The child’s level of comfort may not be where the parents want them to be. Just being “stable and OK” sometimes is enough for them.

Sometimes parents can take their child’s successes and failures personally — try not to do this! We help the parents and family unit to understand how to do self-care — understanding where they are at themselves with their own mental state. For parents, having a willingness to let their kid fail is a big deal. Remember, fear is a major issue and is a big part of how parents make decisions.

Recent Comments